Watching Over Jason: A Sibling’s Story

by Sandra Horne, M.A., M.A.

CCIDS Coordinator for Community Engagement

It’s 839 miles from the front door of my brother’s red brick apartment building to the 1860’s Cape I share with my partner in Downeast Maine. As the COVID-19 virus and its variants continue to spread fear, uncertainty, and the perpetual threat of illness or death into a third year, so goes the stress of watching over Jason, who lives with an intellectual disability in our hometown of Pittsburgh.

Unlike many of us, he’s not afraid of needles and gets his annual flu shot as soon as its available. While Jason isn’t eligible to receive any paid services, his provider did coordinate roundtrip transportation for him to receive both of his COVID shots and a booster. I do my best to keep him supplied with information, hand sanitizer and KN95 face masks. The rest is really up to him.

One of our lowest moments came early in the pandemic. “The library is closed,” he texted. The weight of those four words took a minute to sink in. This preemptive step to prevent the spread of COVID triggered the same dread that a grocery store closure might evoke in others. Having regular access to a public library has always been essential to Jason’s well-being – thousands of books to satiate his curiosity about the natural world; DVD rentals to provide hours of free entertainment; and public computers with free Wi-Fi to compile ambitious Amazon wish lists of things to request from his sister.

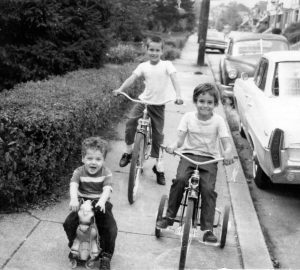

Three of our siblings are gone now and three remain: I’m the eldest of the surviving trio. The youngest is in his mid-fifties and still lives near Pittsburgh, but he’s declined to have any role in Jason’s life. They are hard on each other and quick to anger. At this point in my life, I’ve come to terms with our painful family history of parental mental illness and episodic poverty – a toxic environment for any child, but brutally so for children with disabilities growing up during the 1960’s.

Three of our siblings are gone now and three remain: I’m the eldest of the surviving trio. The youngest is in his mid-fifties and still lives near Pittsburgh, but he’s declined to have any role in Jason’s life. They are hard on each other and quick to anger. At this point in my life, I’ve come to terms with our painful family history of parental mental illness and episodic poverty – a toxic environment for any child, but brutally so for children with disabilities growing up during the 1960’s.

Jason lived with our mother his entire life. They had no interest in or energy for preparing for what life would be like for him after her passing. As they both grew older and more reclusive, they subsisted on her monthly Social Security check, a federal supplemental nutrition assistance program, and a “Senior Box” of staples from the local food pantry. Jason’s refusal to follow through on mandatory counseling for his challenging behavior resulted in a years-long standoff with his case manager.

When our mother died in 2014 on New Year’s Eve, Jason was left on his own with no income, no health insurance, no working relationship with a provider or state agency, and no money to pay the next month’s rent.

The next eight to ten months were terribly hard on both of us. The stress of suddenly being thrust into the role of his social safety net was relentless and nearly wiped me out financially. His lengthy stretches without basic health care came with a price – deteriorating eyesight; numerous tooth extractions; and new conditions of high blood sugar and high cholesterol to understand and manage. And while Jason can tell you the height, weight and length of a Tyrannosaurus Rex, he struggles to understand the dosing instructions on his prescription bottles.

In 2016, he was forced to move from the second-floor apartment he’d shared with my mother for over 20 years when the house was sold by the owner. Today, he’s successfully transitioned to living independently in a studio apartment in another pedestrian-friendly working-class neighborhood about seven miles away. Everything he needs is located within several blocks of his building [and yes, these are in order]: library, bank, grocery store, drug store, dollar store, deli, bakery, pizzeria, hardware store, barber, doctor and hospital.

Honoring Jason’s autonomy sometimes means accepting things I cannot change: his cluttered apartment crammed with dollar store detritus; his unwillingness to consume fewer sugary soft drinks, despite his high blood sugar; and the speed at which he spends his weekly pocket money, leaving him broke most days.

Just before the pandemic struck, Jason had begun to take some small, but consequential steps toward becoming more connected with his community. He volunteered at the library, helping with book sales and donation drives. The men at the local hardware store now know him by name. He’s putting down roots. He’s finding his way. He deserves the right to live a self-determined life: to experience the dignity of risk – to make mistakes – to learn from them and grow. It isn’t easy sometimes. And I watch over him from Maine – hoping he’ll continue to keep himself safe until the dangers posed by COVID and its harmful progeny pass.

Photos courtesy of the author.

Selected Sibling resources

Books

- The Sibling Survival Guide: Indispensable Information for Brothers and Sisters of Adults with Disabilities (2014). Don Meyer and Emily Holl.

Organizations

Podcasts

- Focus on the Future: A Future Planning Podcast of The Arc Minnesota

- Siblings – Our Most Important Relationship (with Don Meyer)

Resources (Online)

- Adult Sibling Toolkit

- Autism Spectrum News: Siblings and Autism (PDF) (Fall 2020)

- Charting the LifeCourse

- Exploring the experiences of siblings of adults with intellectual/developmental disabilities during the COVID‐19 pandemic. (PDF). (October 2020) Journal of Intellectual Disability Research.

- Resources for Siblings of People with Disabilities in New York (PDF)

- Siblings and Future Planning (PDF)

- Sibling Strengths and Supported Decision Making: Updates on Sibling Research

Videos/Webinars

- Brothers and Sisters of People with Disabilities: Unique Concerns, Unique Opportunities [YouTube] (August 2018)

- Faith Jegede: What I’ve Learned From My Autistic Brothers [TED] (April 2012)

- Sib Grief Webinar [YouTube] (September 2019)

- Special Siblings – Documentary Short Film [YouTube] (February 2015)